beer with a painter : Susan Jane Walp

interview by Jennifer Samet https://hyperallergic.com/243546/beer-with-a-painter-susan-jane-walp/

Jennifer Samet: You grew up in Pennsylvania. Do you recall any specific early experiences with art making?

Susan Jane Walp: Yes, I grew up in Allentown, in southeastern Pennsylvania. My earliest memory of having a talent that was recognized was in the third grade. School was very hard for me, and at that time, I don’t remember having any friends in the school itself, although in the neighborhood I was part of an adventuresome group of kids. The class was in charge of decorating a bulletin board with a fall theme. My teacher asked me to make a hunter. It was an incredible experience. I don’t remember doing it for any kind of approval — only for the pleasure of making it — and I loved how it turned out.

The teacher really liked it too, and asked me to do a second one. This time, I had terrible anxiety. I couldn’t get it to look the way that I wanted it to. That was my first experience of what feels like a familiar pattern. Perhaps I was trying to improve the anatomy. You move forward and learn, sometimes at the expense of the inspiration, vitality, and life that come in the beginning of the process.

We were living with my grandparents at the time, and I talked my mother into allowing me to stay home to work on it. I remember working in my pajamas at the kitchen table. I was agonizing over it, but my grandmother and mother were sitting there watching in awe. They could not believe I was able to do what I was doing. My mother’s family was very musical, but they had no visual abilities. In my father’s family, there was a lot of visual talent. My paternal grandmother worked full-time at the family business, and was a very disciplined Sunday painter.

In the third grade I also started taking classes at a very old-fashioned art school in Allentown. It was a beautiful old building with north-facing skylights. It was such a different era back then. My parents would drop me off in inner-city Allentown, and I would walk down the block myself to buy snacks, then come back and buy my charcoal, paper and erasers in the school store. We drew from plaster casts of Greco-Roman sculptures. I felt like such an adult, and very special.

JS: I noticed the small altar in your studio. Does religious practice and meditation play a role in your work?

SJW: Since childhood, I have been interested in religious ideas and practice. My mother’s Austrian family was Lutheran, and I was raised Lutheran. When I was eight, I had a Sunday school teacher, the young wife of the new assistant pastor, who was discussing the idea of the Trinity. She spoke as if she were addressing a group of college students. She presented it as a mystery, as something that she herself was grappling with: how there are three different parts, and yet they are one. These are the things I most remember from childhood, the times when I was taken very seriously by adults.

My paternal grandmother was from a Mennonite background, and I went to a high school run by the Moravians, another Protestant group who established a religious community in Bethlehem, PA, in the early 1700s. Like the Mennonites, they were pacifists and oriented towards education and music. Their motto was “In the essentials, unity; in the non-essentials, liberty; and in all things, love.”

In New York, I became involved with Gurdjieff’s philosophy, and I had a wonderful teacher. After he died in 1983, I moved to rural Vermont with my husband, Michael Moore, and then I spent a long time looking for something. In 2006, I found my way to a recently opened Tibetan Buddhist center in a neighboring town, founded by Dzigar Kongtrul. I have been closely involved with that community for the last ten years. When I go into the studio, I usually begin with a brief meditation. It is a reminder that the inspiration for the work is not so much about me, as it is about being receptive to something that could move through me.

JS: You went to Mount Holyoke for college. Were you studying painting at that time?

SJW: I went to Mount Holyoke in the late 1960s, and there was so much turbulence. I wanted to drop out at a certain point; I was not happy there at all. I had a situation that required surgery, and I missed two and a half months of school. To make up the credits, I went to a program at Tanglewood, run by Boston University. Miraculously, Lennart Anderson was teaching there. The students from BU were very serious, and only because the beginner class was full, I was placed in Lennart’s advanced class. That summer completely changed everything. I saw that my life was going to be devoted to becoming a painter.

Lennart painted in class; he didn’t talk much. But I understood that he was teaching an approach to seeing tonal relationships. It was a very sensual, felt response to the motif. It was about discovering the beauty of these relationships and the thrill of translating them into paint. At the time, he was recommending a Dover book by Charles Hawthorne, Hawthorne on Painting (1960), which we all read and reread.

JS: You also went to the New York Studio School in the early years of the school. What was your experience there?

SJW: I was at the Studio School for about five or six semesters, both during and after Mount Holyoke. It was a wonderful and very intense experience. The daily schedule was very strict — a four-hour session in the morning, another four hours in the afternoon. And many of us continued working well into the evening. The door was locked by 9am, so if you didn’t arrive by then, you couldn’t get in. You worked until 1pm, and then there was a break for lunch. Mercedes Matter would send the kitchen team to Balducci’s for breads, salamis, cheeses, and salad ingredients, and so we had the most amazing, abundant lunches Beginning students spent all eight hours drawing from the model. Nobody spoke in the studios; everyone worked with focus and concentration. I loved the feeling of being part of a like-minded community.

The teachers came in two days a week. Initially I studied drawing with Mercedes, and then I switched over to Nicolas Carone’s class. Mercedes’s teaching was about sensitivity to neighboring relationships, with the image growing out of an accumulation of careful observations. The way that Nick taught was working in the opposite direction: first defining the limits of the plane and the space it contained, and then working from the big forms down towards the detail. Nick taught a kind of metaphysics of space that was not always easy to understand. For me it was about becoming aware of possibilities that existed beyond what one’s habitual mind could ever imagine.

Philip Guston was also teaching at the Studio School at the time. He would make the rounds, moving from studio to studio of the more advanced students, but the beginning students were allowed to follow along and listen in. He hardly ever talked about the students’ paintings! One day, he was visiting the studio at the top of the main stairs; I remember this so clearly. He had brought in a book about Piero della Francesca. I had never heard of Piero della Francesca. He spoke at length about a detail in one of the Arezzo frescoes — an image of hill town rooftops.

I understood Piero immediately — you could say it was love at first sight — and I have since spent a lot of time looking at his work, at first in books and later travelling to see the actual works in Italy and London. The elements in his paintings are so deliberately arrived at—they are spatially and mathematically measured—yet there is simultaneously a strong pattern of shapes moving across the surface. Piero trained in Florence and must have been familiar with the Florentine advances, in terms of three-dimensionality, especially the work of Masaccio

What is interesting to me is that at a relatively young age he returned to his hometown of San Sepolcro, a place that was isolated from Florence and whose church art was influenced by the flatter, more stylized qualities of Sienese art because of trade routes. He chose to retain these qualities that came more from the early Renaissance, even though he could have gone in the direction that eventually led to Leonardo and Michelangelo. The other thing I have found so compelling in his work is how a certain restraint actually intensifies the emotions.

I also remember sitting in the library of the Studio School and looking at a Morandi book. Leland Bell came in and launched into a diatribe, saying I shouldn’t be wasting my time with Morandi. I was fond of Leland and was aware even then that his strong opinions came from how passionate he was about painting and wanting to share that with students. After he left the room, and I started looking at the book again and thought to myself, “I don’t agree with him.” This seemed momentous to me. For the first time it felt like I had confidence in my own mind, and no one was going to talk me out of my inspirations and responses. And I still do love Morandi’s work.

I have gravitated to painters who have lived in provincial settings, like Morandi and Piero. I’m very interested that Agnes Martin moved to an isolated place. Georgia O’Keeffe is another example. I have always been interested in a solitary life, and what that means for an artist who also wants to be part of her time and era. I think, if they could do it, so could I.

JS: I read that you begin paintings in relation to the cycles of the moon. That is fascinating; I have never heard another painter speak of doing this. Can you tell me more about it?

SJW: My Austrian grandmother grew up on a farm and taught me about planting seeds with the phases of the moon. You plant things that grow above ground with the new moon, and things that are harvested for the root, with the full moon. At some point, perhaps after I moved to Vermont and had my own garden, my friend, the painter Helen Miranda Wilson, told me she had been using the cycle of the moon in relation to starting and finishing paintings. I tried it out, and it appealed to me.

With the new moon, which is good for beginnings, I work on finding the motif, painting very freely and openly, trying to get the big gesture and structure of the composition. With the full moon, which is good for completing things, I shift to the fine detail work. When I started working this way, it took away a lot of frustration and confusion. It simplifies things: there is a time for different kinds of activities.

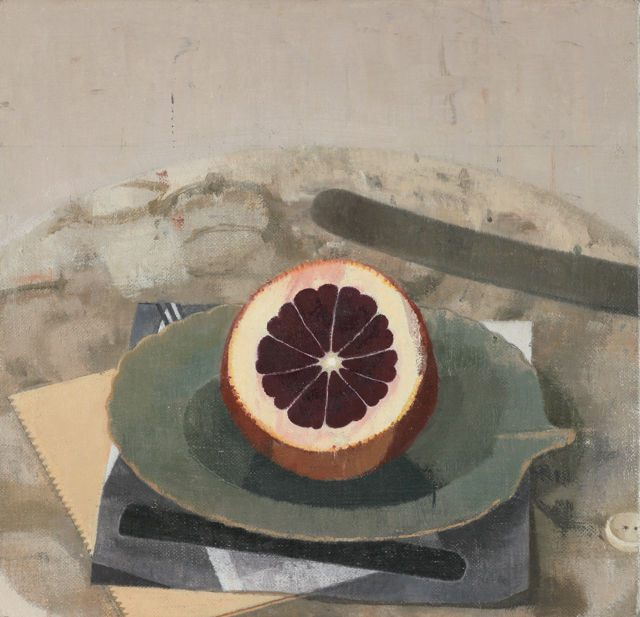

JS: Your still lifes contain certain recurrent objects — blueberries, halved citrus fruits, teacups, and other vessels. Do those objects carry certain personal meanings or significance to you?

SJW: The objects do play a role, but the only way to allow them to truthfully manifest is by seeing them in relationship to all the other elements in the picture. Sometimes, after a painting is complete, meanings are revealed to me. But if my mind moves toward a narrative as I set up the objects, I would resist that.

The thing about working from observation is how abstract it is. We live in a world where we are constantly labeling things and keeping them separate: there is the tree, the fence, and the lawn. But when you get into the painter’s mind, the labels drop away. You are seeing how interconnected everything is, through color and light and space. It is a very wonderful place to be.

A main thing for me is the setting up: arranging and rearranging the objects and waiting for things to come together as an image. With the new moon, this seems to happen reliably. That is the inspiration, and I wait for that moment. I can’t start a painting unless I have that huge feeling of inspiration from the motif. It is very specific; I feel it in my body.

JS: What kind of measuring do you do, as you compose and plan the paintings?

SJW: You could say I am obsessed with measuring. Once the image is there, I want to get as close as possible to the feeling that I have about the motif. At first, I don’t measure at all. The beginnings are very free and spontaneous, and often I will get very accurate measurements intuitively. But nevertheless, for the coming weeks, I measure and re-measure, and draw and redraw. I am not only measuring the forms; I am also measuring the tones, and trying to bring them into a harmony. One might think it is cold and mathematical, but for me it is a very sensual experience.

The big underlying mystery that carries me forward still is how we have this three dimensional experience with the world, and how we put that onto the flat plane of the painting. I have a picture in my mind of how I want that to look in my paintings, and I hardly ever have gotten there. But I still hope that someday I will make a painting that will satisfy me in terms of finding that relationship.

I feel I have always wanted to understand more how shadow and light create form. It hasn’t been very present in my painting, in part because I set up the motif with an even, north light. The light illuminates the form, but it’s subtle, not dramatic. The dramatic use of light and dark to create form is something that has interested me in Euan Uglow’s work. He painted a lot at nighttime, so he had a directional artificial light, which clearly defined areas with beautiful cast shadows that carry so much feeling.

Recently I read something about Morandi that I found to be a revelation. Early in his career, in terms of the other artists he looked at, he really studied chiaroscuro. But in his paintings, as they developed, there is no chiaroscuro, almost the opposite. Everything is bathed in even, inner, mid-tone light, without shadows. And yet that deep knowledge of light and dark is somehow there in the work.

I bring this up as an example of new territory I want to explore. This is the way I have moved forward: responding to these kinds of questions. I am imagining that someday I will set something up and recognize this quality of light and dark I am looking for, because of an Uglow painting that I can’t get out of my mind, or because of a passage I read about Morandi.

Something will trigger a question, and it can take months for me to even articulate it, and more months or years to figure it out. But I feel that conceptual groundwork is so important. As human beings, thinking about things, figuring them out, and putting them into language is central to us. How does that work with this other part of being a painter, which is without language, and without thinking?

beer with a painter : Helen Miranda Wilson

Helen Miranda Wilson: I made pictures almost before I could talk. I knew it was me, in the way that you know what you like to eat, and your favorite color, and what you are attracted to. But I always did it on the side; I didn’t really capitalize on it. I flunked out of Barnard College and worked some shit jobs, and hung out with friends in my hometown. It began to feel like I was on a dead-end street, so I asked myself, “What can I learn to do better, well enough to have it be a job, that I already like to do?” And I applied to the New York Studio School.

The tuition was very low then — about $600 or $700. I asked my father to pay it. Back then, you brought in a portfolio of actual works and a group of faculty would interview you. Leland Bell and Nicolas Carone were there, but by chance, Mercedes Matter, the head of the school, was not in that day. I told them, “I really want to come here and learn to paint and draw from life.” Of course, the thing that was not said was, “And I can pay full tuition.” If I had asked for a scholarship, I probably would not have been accepted.

A month into the first term, I had been trying to learn how to use oil paint. At the first critique review, Mercedes was there. My drawings were in better shape than the paintings — which were mostly small, as they still are by the way, because that’s what I like to do. I am hard-wired for it. Mercedes looked at them, and she looked at me, and her lip curled. She said, “How did you get into this school?” And, turning to the other faculty, said, “Where was I when she was interviewed?”

I had a mother who was very supportive and I didn’t have an inflated ego. So Mercedes’ words did nothing to me. I looked at her and said, “I’m here to learn how to paint.” She fell silent. She was totally disgusted. But by the end of my second year, she offered to buy one of my paintings, which she didn’t usually do for anybody.

JS: Are there specific things your teachers discussed that you still think about?

HMW: We had an eight-hour studio day, which is a lot. It was great. I got just what I needed. When Mercedes was teaching drawing, she was completely immersed in it. She believed in teaching people to see. I cansee, because I went to that school. It is like being able to taste, hear, and feel things by touching them.

One day, I was drawing from the model, and the model’s body was very foreshortened. I was struggling with it, and Carone came over to me and said, “The feet are closer to you than the head.” That was the light bulb. He wasn’t being condescending. You can look at it and measure distances, but, conceptually, you have to think about what you’re working from in three dimensions, and I wasn’t doing that. That was the beginning of really being able to draw from life.

If I’m working outside, for example, I’m trying to get all the different elements down in relation to each other. But, I’m also trying to think about how it all feels, and, if I looked up, how deep it would be up into the sky. That’s the same thing as realizing that the feet are in front of the hip. You have to understand that your eye is reaching through deep space and you have to translate it. I’ve always flattened things. I have an astigmatism. That’s one of the reasons it was so physically sexy for my brain to draw and look into deep space.

"

(...)

The Story of Jonathan Meese

“For me art in school was like chemistry or physics or mathematics. It was totally out of the picture. I was not a good student anyway and not a good, I mean average, I was not really interested in anything. And somehow there, I, it felt easy, and then the process started. And then suddenly people were say to me: “Hey, when you are doing drawings, why don’t you go to this and that museum?” they, “or to the ‘Volkshochschule’? And why don’t you do ‘Aktzeichnen’, drawing naked people?” I said: “Drawing naked people, what? Okay, why not …” Then came these people always telling me something. Like: “Why don’t you, if you are doing this, lithography, why don’t you go to an art school?” I said: “An art school? What is an art school?” And then they told me about this art school in Hamburg. And then they said: “You have to produce a map.” Then I produced a map. And then I was taken – immediately. At that moment there was no struggle. This all happened in one year. I never finished the school, I mean, not with a diploma or something. I just noticed at a certain time in 1995 that you cannot learn art and that you cannot teach art. I mean these five years in art school were very important for me. It was a dark castle building, wonderful. I stayed there overnight. I was always there. I loved it. Many rooms. It as very easy at that time. Everything was dirty. I loved it. The people were really nice. Professors were cool, I really had respect towards my professors even though I think that you cannot be a professor of art, I think this is not possible. I think it doesn’t make sense. Art is the professor. Art doesn’t need a human professor. We had good talks, we had good meals, we had good beer. I also liked some of the artists. Especially my professor, Franz Josef Walter, was super to me, wonderful. We were always talking about wine and food and I was showing him nearly everytime he came my stuff, and he was always laughing. He was so positive, he was alway saying: “Continue, continue, continue, continue” That was all. I was shouting this into the woods and this came back. Exactly what you shout into the woods comes back. If you do what your professor wants you to do then you are dead, you’re finished, you should go home immediately.”

Full transcript :

Breathe! Sleep! Eat! Play! Dream! This is what art says: Play! Use colour! Sleep! Eat a bread! Make heat! Make a fire! Use your umbrealla! That is art. That are the rules, that are the laws. That are the things. Art never tells you: go voting! Art tells you not to be a in a parliament and be a politician. Art doesn’t tell you to be religious in a church. Art tells you to play around, use this, make this, this, this, new costumes, buy things, use your underwear, look at pornography, play with Adolf Hitler, this is what art tells you all the time. Dear picture, do you like yourself? Are you appropriate for these times or the future? Is it ok that you exist? What do you want? That’s the question.

“If you would have a camera here, while I’m working, it would be like a dance.” I love to be alone in my atelier. I don’t want to communicate then. I just want to be the servant of art. And I want the art to talk with each other and with me maybe if they want to. I love this that you are dancing around doing things, always moving and that the paintings scream to you and tell you: “Do a little bit more red here, do blue here!” Then you listen to music and there is this rhythm of something going on that takes care of you, ja? It’s not a trance, because you are there, you know? doing exactly what is necessary. Here you do a little red, here you do a little green, here you glue maybe the umbrella into that painting. Then you have this haaat. I’m always on duty, you know? I’m doing what art wants me to do. And then I’m dancing around, also screaming, talking with myself, always talking about that art should rule the world, that art is the strongest, and art super and wonderful and great, and how beautyful you are, art, and I am here doing my things for you. I am the ant, the animal for art and doing what is necessary. I am one of the biggest “Verdränger”, like a ship, pushing aside problematic stuff. And maybe there were problems. Also I was of course nerved that I looked with 18 like 14 because I was thrown out of every group. Ja? The people thought, oh, the child is coming, uh, bah bah bah. And so I somehow crept into my chair at home and I was always listening to ABBA and the Beatles, and to Deutsch-Amerikanische Freundschaft always to the same songs, like, 3, 4 hours always the same, ja? and very loud and I went into another world. Into the Gegenworld, into the anti-reality. And so I didn’t do so much. I didn’t go into discos. I was always feeling uncomfortable, not old enough, and, but I was also left alone. I mean, I was not tortured or something because I stepped aside. I was quite hermetic. I was not very communicative. I had an own language with 12, which existed out of ten words and three grimasses, faces. [Q:] Could yo show us maybe? [ughhh] [Q:] What does that mean? It’s somehow saying “Leave me alone!” [ugghh] leave me alone, but in a funny way at that time. [ugghhh] Ja und dann “happa happa happa happa” putting this. And then also communicating with putting my hand under the, under this of the people and “khoy, khoy, khoy, khoy”, ja? and doing some words like “dehe”, “doho”, “noninei”, “boitehe”, “jotedei”, funny words that meant nothing. But that’s when I came with 14, 15, 12, 13, this was my way to say: good-bye. I am …, bye-bye. I will survive in a different way. When I was 22, I was like a 14 year old and I was somehow just doing what my mother said to me what I should do. I was more a dreamer and I was … I did not really know what to do. And on this 22nd birthday day, I went with my mother through Hamburg through town and she asked me: “What do you want for birthday present?” And I thought a little bit and then I said: “I want some paper, and some pencils, and, or pastells and I want to start doing paintings, er, drawings.” And my mother looked at me and said: “Hey, why do you want to do drawings? You never, you were never interested in doing art or ….” Even at that moment we didn’t say “art”. “You were never interested in drawing and we have not so much money and it costs a lot of money, these big papers.” But then she bought this. And from that day on I started to paint, to draw, and to make sculptures. I knew somehow that I’m in duty. I didn’t know the words at that moment, I just, I was happy, I knew what I was doing. I loved what I was doing, I felt needed. And I bought, then I immediately started to buy canvasses. I made sculptures out of “Draht” and very simple stuff. I only knew Picasso at that time and Salvador Dali. And I started to draw like in these “Stierkampf” sceneries, these bullfighting sceneries. And for me Picasso was art. I didn’t know anything more. I stopped doing art in school when I was 16, 17. I was totally average. For me art in school was like chemistry or physics or mathematics. It was totally out of the picture. I was not a good student anyway and not a good, I mean average, I was not really interested in anything. And somehow there, I, it felt easy, and then the process started. And then suddenly people were say to me: “Hey, when you are doing drawings, why don’t you go to this and that museum?” they, “or to the ‘Volkshochschule’? And why don’t you do ‘Aktzeichnen’, drawing naked people?” I said: “Drawing naked people, what? Okay, why not …” Then came these people always telling me something. Like: “Why don’t you, if you are doing this, lithography, why don’t you go to an art school?” I said: “An art school? What is an art school?” And then they told me about this art school in Hamburg. And then they said: “You have to produce a map.” Then I produced a map. And then I was taken – immediately. At that moment there was no struggle. This all happened in one year. I never finished the school, I mean, not with a diploma or something. I just noticed at a certain time in 1995 that you cannot learn art and that you cannot teach art. I mean these five years in art school were very important for me. It was a dark castle building, wonderful. I stayed there overnight. I was always there. I loved it. Many rooms. It as very easy at that time. Everything was dirty. I loved it. The people were really nice. Professors were cool, I really had respect towards my professors even though I think that you cannot be a professor of art, I think this is not possible. I think it doesn’t make sense. Art is the professor. Art doesn’t need a human professor. We had good talks, we had good meals, we had good beer. I also liked some of the artists. Especially my professor, Franz Josef Walter, was super to me, wonderful. We were always talking about wine and food and I was showing him nearly everytime he came my stuff, and he was always laughing. He was so positive, he was alway saying: “Continue, continue, continue, continue” That was all. I was shouting this into the woods and this came back. Exactly what you shout into the woods comes back. If you do what your professor wants you to do then you are dead, you’re finished, you should go home immediately. The mother is always the total authority and we have to be total families in this and you should never be against your mother or your parents. Whatever comes, please take them! I mean, there are constellations that are difficult sometimes, but this is natural friendship, this has to be on the highest possible level. That’s why I don’t like the people from 1968. I don’t like the people from 1968 who were against their parents Even if the parents did bad things, no, you have to find another solution. You cannot be against your parents. Because they are the weak ones. My mother is total authority naturally. There are authorities, but natural ones we need, not ideological authorities. We think we are too important. We have to put ourselves into the “Nahrungskette”, into the nourishing chain And there mymother is standing here [high], always, and I stand here [lower]. I will never be above her, never, never, even if she dies. And she always says: “Jonathan, it’s ok that you have so much pro-no-gra-phy.” which is really strange for her because she is 81 years old, she comes from another generation, and she connects it to money. She says, or succes, she says: “Jonathan, you are so successfull, that’s why you can have it.” Otherwise I would be a pervert for her. I think I’m not a pervert because for me it’s all material. Even if I would be a pervert, it’s also okay as long as it’s in an art. As long as it’s not a reality-pervert. The anti-reality can suck up all perversion. My mother is totally pragmatic. That’s why she comes with this money aspect. She says, not because she’s greedy or something, she says: “It’s good, Jonathan, what you do because you are accepted, the people love you, they pay a lot of money for what you are doing and then we can keep this up and we have a family and, great.” She also likes some paintings, some she doesn’t, she’s also working often her, I make portraits of her, I use her also in sculptures and sometimes we even paint somehow together. I just paint a little and then she says: “Stop it now, finished.” And when an authority like her capacity says finished, then I say ok. My father is too utopian I mean, I met my father many times. He stayed in Japan, he was an Englishman, very handsome, very funny. He was somehow an artist, but he never lived it. He was often in banks, working for banks. And he died 20 years ago. He died when I was 18, 19 and I was too shy to speak to him. I always admired him, looked at him, also visited him in Japan. I was always lying under a table in Japan, I remember I was very sleepy person, I was always sleeping. And when I was sleeping in a bed, and in the morning I just went into the room where he stayed and had breakfast with a hairnet and reading newspaper in a gown like a kimono then I was just slipping into the room under the table It’s heated under the table in Japan often. I was just like sleep-sitting there looking at him. For me he was like Hercule Poirot. Somehow he had this face very oldfashoined face very beautiful and I was too shy to talk with him because he cold only speak Japanese and English and I only spoke German and not very good English And I was so afraid to make a mistake in front of my father that I didn’t talk with him. Whoah, I was paralized. Now I could talk with him. But till he died, I couldn’t talk with him. Not too much. He always gave me presents, the newest stuff from Japan a walkman, things like this. The reality made his life at a certain point quite difficult and not really enjoyable because he was too mixed up trying to be too perfect. The pressure is very high in reality. [Q:] If your father had been alive today, do you think it would have changed the way you live? Maybe I would have been a banker now, ja. [Q:] You think you would have been a good banker? I think so, ja.. Ja, with total passion.

JEAN-BAPTISTE-SIMEON CHARDIN: TO THE ACADEMY JURY

http://homepages.neiu.edu/~wbsieger/Art316/316Read/Chardin.pdf

from E. and J. de Goncourt’s: French Eighteenth-Century Painters

Chardin is, par excellence, the simple good fellow among the artists of his time. Modest in the midst of success, he liked to repeat the phrase:‘Painting is an island whose shores I have skirted’ He was quite without jealousy and surrounded himself with pictures and drawings by his fellow-artists. He was fatherly towards young men and judged their youthful efforts with indulgence. Those charities which are an attribute of genuine talent dwelt in his mind and heart. The quality of his goodness has been handed down to us, vivid and vibrating, in the words recorded by Diderot. They must be quoted here as showing us the essence of the man and the spirit of the artist:

Gentlemen, you should be indulgent. Among all the pictures here, seek out the worst ones; and know that a thousand unhappy painters have broken their brushes between their teeth out of despair at never being able to do as well. Parrocel, whom you call a dauber, and who indeed is one, if you compare him to Vernet, is nevertheless also an exceptional man, relatively to the multitude of those who have abandoned the career upon which they entered in his company. Lemoine used to say that the ability to retain in the finished picture the qualities of the preliminary sketch required thirty years of practice, and Lemoine was not a fool. If you will listen to what I have to say, you may learn, perhaps, to be indulgent. At the age of seven or eight, we are set to work with the pencil-holder in our hands. We begin to draw, from copybooks--eyes, mouths, noses, ears, and then feet and hands. And our backs have been bent to the task for a seeming age by the time we are confronted with the Farnese Hercules or the Torso; and you have not witnessed the tears provoked by the Satyr, the Dying Gladiator, the Medici Venus, the Antaeus. Believe me when I tell you that these masterpieces of Greek art would no longer excite the jealousy of artists if they had been exposed to the resentment of students. And when we have exhausted our days and spent waking, lamp-lit nights in the study of inanimate nature, then living nature is placed before us and all at once the work of the preceding years is reduced to nothing: we were not more constrained than on the first occasion on which we took up the pencil. The eye must be taught to look at Nature; and how many have never seen and will never see her! This is the anguish of the artist's life. We work for five or six years from the life and then we are thrown upon the mercy of our genius, if we have any. Talent is not established in a moment. It is not after the first attempt that a man has the honesty to confess his incapacity. And how many attempts are made, sometimes fortunate, sometimes unhappy! Precious years may glide away before the day arrives of weariness, of tedium, of disgust. The student may be nineteen or twenty when, the palette falling from his hands, he finds himself without a calling, without resources, without morals; for it is impossible to be both young and virtuous, if nature, naked and unadorned, is to be an object of constant study. What can he then do, what can he become? He must abandon himself to the inferior occupations that are open to the poor or die of hunger. The first course is adopted; and, with the exception of an odd twenty who come here every two years and exhibit themselves to the foolish and the ignorant, the others, unknown and perhaps less unhappy, carry a musket on their shoulders in some regiment, wear a fencing pad on the chest in some school of arms, or the costume of the stage at some theatre. What I am telling you was in fact the fate of Belcourt, Lekain and Brizard, who became bad actors in despair of becoming mediocre painters.

And he recounted with a smile how one of his colleagues, whose son was a drummer in a regiment, would reply to those who asked for news of him that he had abandoned painting for music; and then, resuming a serious tone, he added:

All the fathers of such strayed and incapable children do not take it so lightly. What you see here is the fruit of the labours of the small number who have struggled more or less successfully. The man who has never felt the difficulty of art achieves nothing of value; and he who, like my son, has felt it too much, does nothing at all; let me assure you that every superior rank or condition in society would be a mockery if admission did not require tests as severe as those to which artists are subjected…. Goodbye, gentlemen, and I beg you to be indulgent, always indulgent.

from E. and J. de Goncourt’s: French Eighteenth-Century Painters

Chardin is, par excellence, the simple good fellow among the artists of his time. Modest in the midst of success, he liked to repeat the phrase:‘Painting is an island whose shores I have skirted’ He was quite without jealousy and surrounded himself with pictures and drawings by his fellow-artists. He was fatherly towards young men and judged their youthful efforts with indulgence. Those charities which are an attribute of genuine talent dwelt in his mind and heart. The quality of his goodness has been handed down to us, vivid and vibrating, in the words recorded by Diderot. They must be quoted here as showing us the essence of the man and the spirit of the artist:

Gentlemen, you should be indulgent. Among all the pictures here, seek out the worst ones; and know that a thousand unhappy painters have broken their brushes between their teeth out of despair at never being able to do as well. Parrocel, whom you call a dauber, and who indeed is one, if you compare him to Vernet, is nevertheless also an exceptional man, relatively to the multitude of those who have abandoned the career upon which they entered in his company. Lemoine used to say that the ability to retain in the finished picture the qualities of the preliminary sketch required thirty years of practice, and Lemoine was not a fool. If you will listen to what I have to say, you may learn, perhaps, to be indulgent. At the age of seven or eight, we are set to work with the pencil-holder in our hands. We begin to draw, from copybooks--eyes, mouths, noses, ears, and then feet and hands. And our backs have been bent to the task for a seeming age by the time we are confronted with the Farnese Hercules or the Torso; and you have not witnessed the tears provoked by the Satyr, the Dying Gladiator, the Medici Venus, the Antaeus. Believe me when I tell you that these masterpieces of Greek art would no longer excite the jealousy of artists if they had been exposed to the resentment of students. And when we have exhausted our days and spent waking, lamp-lit nights in the study of inanimate nature, then living nature is placed before us and all at once the work of the preceding years is reduced to nothing: we were not more constrained than on the first occasion on which we took up the pencil. The eye must be taught to look at Nature; and how many have never seen and will never see her! This is the anguish of the artist's life. We work for five or six years from the life and then we are thrown upon the mercy of our genius, if we have any. Talent is not established in a moment. It is not after the first attempt that a man has the honesty to confess his incapacity. And how many attempts are made, sometimes fortunate, sometimes unhappy! Precious years may glide away before the day arrives of weariness, of tedium, of disgust. The student may be nineteen or twenty when, the palette falling from his hands, he finds himself without a calling, without resources, without morals; for it is impossible to be both young and virtuous, if nature, naked and unadorned, is to be an object of constant study. What can he then do, what can he become? He must abandon himself to the inferior occupations that are open to the poor or die of hunger. The first course is adopted; and, with the exception of an odd twenty who come here every two years and exhibit themselves to the foolish and the ignorant, the others, unknown and perhaps less unhappy, carry a musket on their shoulders in some regiment, wear a fencing pad on the chest in some school of arms, or the costume of the stage at some theatre. What I am telling you was in fact the fate of Belcourt, Lekain and Brizard, who became bad actors in despair of becoming mediocre painters.

And he recounted with a smile how one of his colleagues, whose son was a drummer in a regiment, would reply to those who asked for news of him that he had abandoned painting for music; and then, resuming a serious tone, he added:

All the fathers of such strayed and incapable children do not take it so lightly. What you see here is the fruit of the labours of the small number who have struggled more or less successfully. The man who has never felt the difficulty of art achieves nothing of value; and he who, like my son, has felt it too much, does nothing at all; let me assure you that every superior rank or condition in society would be a mockery if admission did not require tests as severe as those to which artists are subjected…. Goodbye, gentlemen, and I beg you to be indulgent, always indulgent.

On the Perfection Underlying Life

http://anneflournoy.com/agnes-martins-notes/

And without desire there is hope.

These bones will rise again.

Undefeated you will have nothing to say but more of the same.

Defeated you will stand at the door of your house to welcome the unknown, putting behind you all that is known.

Defeated having no place to go you will perhaps wait and be overtaken.

Agnes Martin’s notes for “On the Perfection Underlying Life”

This lecture was originally given at the ICA on February 14, 1973 on the occasion of the exhibition, “Agnes Martin” which was held at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, January 22 – March 1, 1973. ©2009 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beginning No. 5

The process of life is hidden from us. The meaning of suffering is held from us. And we are blind to life.

We are blinded by pride. Pride has built another structure and it is called “Life” but living the prideful life we are frustrated and lost.

It is not possible to overthrow pride. It is not possible because we ourselves are pride; Pride the Dragon and Pride the Deceiver as it is called in Mythology. But we can witness the defeat of pride because pride can not hold out. Pride is not real so sooner or later it must go down.

When pride in some form is lost we feel very different. We feel the victory over pride, and we feel very different being for a few moments free of pride. We feel a moment of perfection that is indescribable, a sudden joy in living.

Our best opportunity to witness the defeat of pride is in our work, in all the time that we are working and in the work itself.

Work is self-expression. We must not think of self expression as something we may do or something we may not do. Self expression is inevitable. In your work, in the way that you do your work and in the result of your work yourself is expressed. Behind and before self expression is a developing awareness I will also call “the work”. It is the most important part of the work. There is the work in our minds, the work in our hands and the work as a result.

In your work, in everyone’s work, in the work of the world, the work that reminds of pride is gradually abandoned. Having in moments of perfection enjoyed freedom from pride we know that that is what we want. With this knowing we recognize and eliminate expressions of pride.

I will now speak directly to the art students present as an illustration of the work with particular references to art work.

My interest and yours is art work, works of art, every smallest work of art and every kind of art work. We are very interested, dedicated in fact. There is no halfway with art. We wake up thinking about it and we go to sleep thinking about it.

We go everywhere looking for it, both artists and non-artists. It is very mysterious the fast hold that it has upon us, considering how little we know about it. We do not even understand our own response to our own work.

Why do we go everywhere searching out works of art and why do we make works of art. The answer is that we are inspired to do so.

When we wake up in the morning we are inspired to do some certain thing and we do do it. The difficulty lies in the fact that it may turn out well or it may not turn out well. If it turns out well we have a tendency to think that we have successfully followed our inspiration and if it does not turn out well we have a tendency to think that we have lost our inspiration. But that is not true. There is successful work and work that fails but all of it is inspired. I will speak later about successful works of art but here I want to speak of failures. Failures that should be discarded and completely cut off.

I have come especially to talk to those among you who recognize these failures. I want particularly to talk to those who recognize all of their failures and feel inadequate and defeated, to those who feel insufficient – short of what is expected or needed. I would like somehow to explain that these feelings are the natural state of mind of the artist, that a sense of disappointment and defeat is the essential state of mind for creative work.

In order to do this I would like to consider further those moments in which we feel joy in living. To some these moments are very clear and to others of a vagueness that can only be described as below the level of consciousness. Whether conscious or unconscious they do their work and they are the incentive to life. A stockpile of these moments gives us an awareness of perfection in our minds and this awareness of perfection in our minds makes all the difference in what we do.

Moments of perfection are indescribable but a few things can be said about them. At such times we are suddenly very happy and we wonder why life ever seemed troublesome. In an instant we can see the road ahead free from all difficulties, and we think that we will never lose it again. All this and a great deal more in barely a moment, and then it is gone. But all such moments are stored in the mind. They are called sensibility or awareness of perfection in the mind.

We must surrender the idea that this perfection that we see in the mind or before our eyes is obtainable or attainable. It is really far from us. We are no more capable of having it than the infant that tries to eat it. But our happiness lies in our moments of awareness of it.

The function of art work is the stimulation of sensibilities, the renewal of memories of moments of perfection.

There is only one way in which artists can serve this function of art. There is only one way in which successful works of art can be made. To make works of art that stimulate sensibilities and renew moments of perfection an artist must recognize the works that illustrate his own moments of perfection.

Perfection, of course, cannot be represented. The slightest indication of it is eagerly grasped by observers. The work is so far from perfection because we ourselves are so far from perfection. The oftener we glimpse perfection or the more conscious we are in our awareness of it the farther away it seems to be. Or perhaps I should say the more we are aware of perfection the more we realize how very far away from us it is. That is why art work is so very hard. It is a working through disappointments to greater disappointment and a growing recognition of failure to the point of defeat. But still one wakes in the morning and there is the inspiration and one goes on.

I want to emphasize the fact that increase in disappointment does not mean going backward in the work. There is no such thing as backward in anything. There is increased and decreased awareness that is all and increased awareness means increased disappointments. If any perfection is indicated in the work it is recognized by the artist as truly miraculous so he feels that he can take no credit for its sudden appearance.

What does it mean to be defeated. It means that we cannot go on. We cannot make another move. Everything that we thought we could do we have done without result. We even give up all hope of getting the work and perhaps even the desire to have it.

But we still go on without hope or desire or dreams or anything. Just going on with almost no memory of having done anything.

Then it is not us.

Then it is not I.Then it is not conditioned response.Then there is some hope of a hint of perfection.And without desire there is hope.

These bones will rise again.

Undefeated you will have nothing to say but more of the same.

Defeated you will stand at the door of your house to welcome the unknown, putting behind you all that is known.

Defeated having no place to go you will perhaps wait and be overtaken.

Without hope there is hope.

We do not ever stop because there is no way to stop. No matter what you do you will not escape. There is no way out. You may as well go ahead with as little resistance as possible – and eat everything on your plate. Going on without resistance or notions is called discipline. Going on when hope and desire have been left behind is discipline. Going on in an impersonal way without personal considerations is called discipline.

Not thinking, planning, scheming is a discipline. Not caring or striving is a discipline.

Defeated you will rise to your feet as is said of Dry Bones

As in the night. To penetrate the night is one thing. But to be penetrated by the night. That is to be overtaken.

Defeated, exhausted, and helpless you will perhaps go a little bit further.

Helplessness, even a mild state of helplessness is extremely hard to bear. Moments of helplessness are moments of blindness. One feels as tho something terrible has happened without knowing what it is. One feels as tho one is in the outer darkness or as tho one has made some terrible error a fatal error. Our great help that we leaned on in the dark has deserted us and we are in a complete panic and we feel that we have got to have help.

The panic of complete helplessness drives us to fantastic extremes and feelings of mild helplessness drives us to ridiculousness. We go from reading religious doctrine and occult practices to changing our diet. Or from absolute self abasement or abandonment to ever known and unknown fetish.

It is so hard to realize at the time of helplessness that that is the time to be awake and aware. The feeling of calamity and loss covers everything. We imagine that we are completely cut off and tremble with fear and dread. The more we are aware of perfection the more we will suffer when we are blind to it in helplessness.

But helplessness when fear and dread have run their course, as all passions do, is the most rewarding state of all. It is a time when our most tenacious prejudices are overcome. Our most tightly gripped resistances come under the knife, and we are made more free. Our lack of independence in helplessness is our most detrimental weakness from the standpoint of art work. Stated positively, independence is the most essential character trait in an artist.

Although helplessness is the most important state of mind, the holiday state of mind is the most efficacious for artists: “Free and easy wandering” it is called by the Chinese sage Chuang Tzu. In free and easy wandering there is only freshness and adventure. It is really awareness of perfection within the mind. Everyone has memories of adventures within the mind, strange and pleasant memories, but not everyone is aware of adventures within the mind when they happen.

I want to recommend the exploration of mind and the adventure within the mind. It takes so much time; that is the difficulty. It is so hard to slow down to the pace where it is possible to explore one’s mind. And then of course one must go absolutely alone with not one thought about others intruding because then one would be off in relative thinking.

Being an artist is a very solitary business. It is not artists that get together to do this or that. Artists just go into their studios everyday and shut the door and remain there. Usually when they come out they go to a park or somewhere where they will not meet anyone. A surprising circumstance? That I will try to explain.

The solitary life is full of terrors. If you went walking with someone that would be one thing but if you went walking alone in a lonely place that would be an entirely different thing. If you were not completely distracted you would surely feel “the fear” part of the time. I am not now speaking of the fear and dread of helplessness which is a very unusual state of mind. I am speaking of pervasive fear that is always with us. It is a constant state of mind of which we are not aware when we are with others. We are used to this fear and we know that when we are with anyone else, even a stranger, we do not have it. That is all that we do know about it. In solitude this fear is lived and finally understood.

Worse than the terror of fear is the Dragon. The Dragon really pounds through the inner streets shaking everything and breathing fire. The fire of his breath destroys and disintegrates everything. The dragon is undiscriminating and leaves absolutely nothing in his wake.

The solitary person is in great danger from the dragon because without an outside enemy the dragon turns on the self. In fact self destructiveness is the first of human weaknesses. When we know all the ways in which we can be self destructive that will be very valuable knowledge indeed.

The terrible thing is that we are not just the dragon but the victim even when he is destroying someone else, and our suffering is according to just how destructive he feels. So we cannot afford one moment of antagonism about anything.

I hope that it is quite plain that I am not moralizing, but simply describing some of the states of mind that are a hazard in solitude.

Sometimes through hard work the dragon is weakened. The resulting quiet is shocking. The work proceeds quickly and without effort. But at anytime the Dragon may rouse himself and then one is driven from the studio. If he can then have a good contest with someone else he is thoroughly aroused and the next day his victories go round and round in the mind. I am sure you have noticed it. But if he only goes to the park he does not get completely roused and the next day he will perhaps be quiet.

We cannot and do not slay the Dragon that is a medieval idea, I guess. We have to become completely familiar with him and hope that he sleeps. The way things are most of the time is that he is awake and we are asleep. What we hope is the opposite.

I have known some very young artists who are familiar with the Dragon and know many of his ways. They also recognize fear and are independent of judgement. They recognize themselves as mere shadows in reality. They like to be alone and seem to have had plenty of practice of being alone since early childhood. All that is a tremendous head start in art work and these artists are correctly recognized as geniuses.

We will all get there someday however and do the work that we are supposed to do. Of all the pitfalls in our paths and the tremendous delays and wanderings off the track I want to say that they are not what they seem to be. I want to say that all that seems like fantastic mistakes are not mistakes and all that seems like error is not error, and it all has to be done. That which seems like a false step is just the next step.

You may as well give up judging your actions. If it is the unconditioned life that you want you do not know what you should do or what you should have done. We will just have to let everything go. Everything we know and everything everyone else knows is conditioned. The conditioning goes all the way back through evolution. The conditioned life, the natural life and the conventional life are the same.

Say to yourselves. I am going to work in order to see myself and free myself. While working and in the work I must be on the alert to see myself. When I see myself in the work I will know that that is the work I am supposed to do. I will not have much time for other peoples problems. I will have to be by myself almost all the time and it will be a quiet life.

Success is contentment with no discontentment about anything: anything in the work or anything outside the work.

What was the reaction of the person who first made a symmetrical house. He felt new contentment in the house. He could see that it reflected himself. He felt a satisfaction in having built it and perhaps an awareness of clarity in his mind as the means. (A contentment with oneself that is success. Do not stop short of real contentment. You may as well never have been born if you remain discontented.)

Perfection is not necessary. Perfection you can not have. If you do what you want to do and what you can do and if you can then recognize it you will be contented. You cannot possibly know what it will be but looking back you will not be surprised at what you have done.

For those who are visual minded I will say. There seems to be a fine ship at anchor, fear is the anchor, convention is the chain, ghosts stalk the decks, the sails are filled with pride and the ship does not move.

But there are moments for all of us in which the anchor is weighed. Moments in which we learn what it feels like to move freely not held back by pride and fear. Moments that can be recalled with all their fine flavour.

The recall of these moments can be stimulated by freeing experiences including the viewing of works of art.

Artists try to maintain an atmosphere of freedom in order to represent the perfection of those moments. And others searching for the meaning of art respond by recalling their own free moments.

I hope I have made clear that the work is about perfection as we are aware of it in our minds but that the paintings are very far from being perfect – - completely removed in fact – - even as we ourselves are.

Inscription à :

Commentaires (Atom)